Tippco ‘Ford Model B’ farm truck, donated by Henry Jackson Mason, Te Manawa Museums Trust, 84/13/1.

Family trees tend to have skewed growth. Some branches are sparse, with names of elusive relatives; others have a rich foliage of daring adventures and intrepid tales. The branch extended to me via my granddad, Harry Mason, was one of the hefty branches, so it was no surprise to find objects from his childhood gracing the collection in Te Manawa.

The Toy Truck

The truck pictured above, a wind-up tin replica of a Ford Model B, was made by Tippco, a German toy company founded in Nuremberg in 1912. It has a tipping tray at the back painted in sky blue and red, with a yellow uniformed driver behind the wheel. Around the rims of the tyres are the words DUNLOP CORD 865 X 135. Tied to the front is a piece of string; we can imagine a young Harry pulling it around. In the tray is a handmade wool bale he stitched himself, possibly with the help of his mother – a DIY embellishment that I recognise in the granddad I knew as a much older man.

A truck may seem like a common toy for a young boy growing up in Depression-era New Zealand. But this truck, in particular the personal touch, brings to light a real-life tale of “pioneering spirit”.

Settling in the remote Taunoka valley

The Mason family lived in the Taunoka valley in the Taumatamahoe district, 54 miles (87 kilometres) inland from Whanganui. The Crown acquired the land through dubious means from Whanganui iwi, under a government interested in developing routes for the main trunk line and State Highway 1 through this area.[i] In 1917 the nearby Mangapūrua soldiers’ settlement opened up for conversion from virgin bush to pastoral farming, to provide soldiers returning from the First World War with a block of land.

My great grandfather, Jackson Mason, had been spared the tortures of war because of his farming prowess, and was stationed in the area to help with its development. After losing his first wife and new baby to the Spanish flu in 1918, he took up a post as an early settler in the valley. He leased land from the Crown to aid the transformation of old growth backcountry bush into a potentially profitable farm. He called his farm Okoroa, after the nearest trig point, and took with him his new wife, Edith, my great-grandmother.

Many describe these settlements as a failure. The land was infertile, steep, and prone to erosion because the bush had been cleared. It was common for farmers, after years of back-breaking work, to walk off the land with nothing. In retrospect, the lack of care for returned servicemen’s needs, the destruction of the old forest, the loss of kai gathering grounds for local Māori, and the loss of their lands, were all evidence of the scheme’s major shortcomings.

Childhood in the Taunoka valley

Harry was born into this remote farming life with his twin sister, Tui. She was to be one of his few companions in this isolated area, full of natural wonder, intrepid tales and the kind of DIY creativity that characterised him. Through my great-grandmother Edith’s diaries, published by Harry in 1988, our family can read tales of the twins’ childhood.

They had no pretty clothes to spoil and would make mud pies and slosh around in the stream. I really believe they loved the life, Harry with his few toys and Tui always doing something. As they grew older their games centered around the farm. They had some lovely books, mostly from my family and Jack’s Aunt Ada and Uncle Herbert Jackson.[ii]

My own memories of granddad’s sheds, with number 8 wire wrapped around everything and a hundred uses for an old tin can, are relics of my childhood.

From the start the two children grew up to be independent, naturally developing the ability to involve themselves in their own interests and share work and play with each other. From tiny tots they learnt that they were expected to help around the home, and they would follow their father into the sheep yards and the milking sheds.

The rhythms of the farm were so entrenched in these children’s minds that they described gathering gooseberries as ‘mustering’ the berries, and topping and tailing them for jam making as ‘docking’. They would also build miniature sheep yards and draft races with their blocks.

The toy that replicates real life

Edith’s family lived at Maraekakaho Station, west of Hastings, and every Christmas the family would leave the back country farm and visit. It was here, in the early 1930s, that under the Christmas tree lay a toy tin truck with Harry’s name on it.

Until 1931, the only route into and out of Okoroa was via the river, first on a steam boat and then along a muddy path. Edith described the journey as a lovely walk of six miles, through magnificent scenery, with huge bluffs on one side nearly all the way, and the track cut along the edge of the cliff dropping into the great gorge. There were times when the track was all but washed out, and those traveling it would rely on the steadfast hooves of their horses to get them through.

In 1931 the watershed road at the back of the Taunoka valley was completed, and in December that year the first lorry-load of wool was sent out from Taunoka station. Edith’s diaries described it as being “wonderfully exciting and certainly a grand saving of time and labour”.[iii]

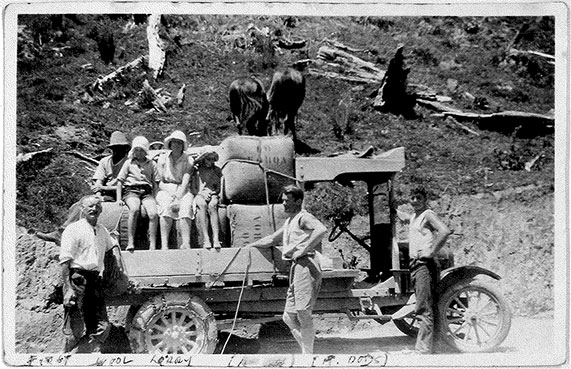

The photograph below depicts this event. It is 1931, a sunny and warm December day, with everyone dressed in light clothes and sunhats. The truck is stacked high with bales of wool stamped with the label OKOROA. Harry sits on top of the bales, flanked on one side by his father Jackson, and Enid, a correspondence school tutor who was visiting at the time. Tui perches on the end of the row. In the front of the loaded truck are neighbours and helpers on the farm: Charlie Menifee, Angus Dodds and Ray Guilford. Behind the truck are two horses on a well-deserved break from the twelve mile round trip to deliver bales to the steamboat on the Whanganui River.

Walking off the farm

Less than ten years after this photo was taken, the Mason family abandoned the farm. In 1940 they packed their bags, including the toy truck. A combination of the crash in agricultural prices and the start of the Second World War, pulling young men out of the district, meant that leaving was the only viable option. After 20 years of work the family enterprise ended, owing 29 pounds, 10 shillings and 9 pence. The last of the settlers left the area in 1942. A bridge – now known as ‘the bridge to nowhere’ – over the Mangapūrua Gorge is one of the few remaining traces of the area being formerly settled.

[i] Stephen Oliver, Taumatamahoe Block Report: A Report Written for the Waitangi Tribunal, Wai 903, A 42, August 2003; accessed 18 June 2023.

[ii] Harry Mason and Arthur P. Bates, Okoroa: A Wanganui River Diary, Wanganui Newspapers Ltd, 1988, p. 55.

[iii] Mason and Bates, p. 122.