I should connect the book to the exhibition. The book came first, focused on Marti Friedlander’s portraits of artists and writers, potters, people involved in dance and music. In late 2019 Jeanine Parkinson, director of the Portrait Gallery in Wellington asked me, have you got any ideas for an exhibition? And it was perfect. There were about 80 photographs in that exhibition at the Portrait Gallery. It toured to Waikato Art Museum, Stratford North, Te Uru in Auckland, Suter in Nelson, then smaller versions at the Northern Club in Auckland. What we have here is much reduced in terms of the number of photo portraits by Marti Friedlander, and what I thought was a wonderful idea, to pair the photo of a particular artist with a work by that artist. I only first saw this show this morning, and what struck me was, why hadn’t anyone thought of it before? To me it works brilliantly.

Marti, before she took up photography, initially went to the Camberwell School of the Arts in London, but realised pretty quickly she wasn’t going to be much of an artist. Quite by chance she was accepted into a photography course because they had a spare place, and then worked with a couple of very good photographers in London as their studio assistant, which involved a lot of the printing. She had a long apprenticeship in terms of developing negatives and touching up work. One was Gordon Crocker, largely a fashion photographer, who was very much in loco parentis; a father figure in a way. The other was Douglas Glass, a New Zealand-born artist who’d never returned, saying he hated New Zealand. Initially he was an abstract painter, possibly the first abstract painter of New Zealand birth in Britain, but then he became a photographer, and for many years he was the portrait photographer for the Sunday Star Times in London. A brilliant portraitist. So Marti had very close and immersive training, in materials and techniques, and the business of making portrait photographs

Coming to New Zealand, initially she was at a bit of a loss, but because she was very much involved with the arts generally in London in the ‘40s and ‘50s, she quickly noticed that in our very small art world, artists and writers – and creative people generally, really – didn’t get the recognition you would expect in a large country. New Zealand is only a couple of million people at that point. So from early on, this was quite a conscious and deliberate project to take as many photographs of artists and writers, potters and musicians and so on as she could.

The first one that was published was in 1959, of Maurice Gee, which is in the book. Serendipity seemed to play a large role; she was living in Henderson, which was more of a town on the fringes of Auckland then, where her husband was working as a dentist – they made a pretty idiosyncratic couple. By chance next door lived Maurice Gee’s parents, and Maurice happened to come by on his way to Australia. He was just beginning as a writer. She took a series of photographs of him, and if you look at the book you can see she was born for this almost, allowing for her training. As was so often the case with her best photographs (I say “best” photographs; she could be very critical of her own work, in fact could be very dismissive), there’s an uncanny element here, somehow bringing out the conflicting or contradictory qualities within a person. Standard commercial portrait photography is straight up and down, people want photographs in which they look good, so they were often flattering and carefully posed and so on in a studio. Marti was among the first – she liked being called a photographer, she didn’t like being called an artist – who moved away from pretty formulaic standard, often stereotypical, portrait modes. All the photographs here except one are taken in domestic situations: either their houses or studios or nearby where the artist happened to be living or staying.

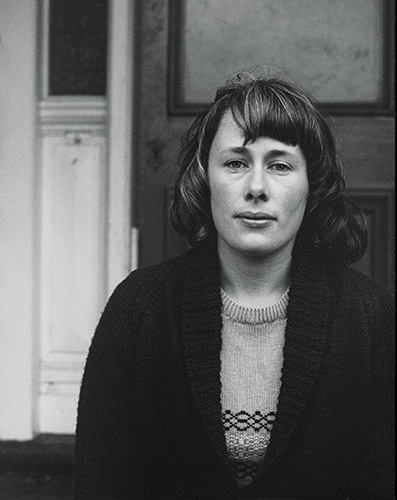

This one of Robin White from 1968 – Robin had just completed art school – shows a typical colonial-era house in Auckland, in Mt Eden. And what [exhibition developer] Talei has ingeniously done is pair it with this graphic work by Robin White below of a more inter-war house at Kaitangata, south of Dunedin, where she was living in the late 1970s. So here we have Robin, a very composed person. Sometimes she seems shy but very assured, and she has been very influential. She has had an extraordinary career, in terms of her own work and also as a teacher, mentor and guide. And there she is at about 24 or so, at the start of what was going to be a very successful career, looking directly back at us. I feel those qualities I just attributed to her visualised in the photograph too.

Marti Friedlander, Robin White, Auckland, 1968

Marti had the ability with her best photographs, and I think this is particularly evident in her photos of artists and writers, of going beyond the surface. There is a sense of interiority, of the inner qualities of the person, which mightn’t necessarily be immediately evident; you might not even be conscious of them. These best portraits allow us to spend time with faces, endlessly intriguing faces of creative and complex people.

Here’s Grahame Sydney, out there in central Otago with what looks like a wrecked tram carriage. How did that end up there? But this is wonderful, this pairing: it’s a chilling kind of painting. People speak of “New Zealand Gothic”, but there are intimations without labouring it. In the book there’s one of Grahame Sydney and his wife sitting on a bed and looking back at us, slightly apprehensive. So Marti had inveigled her way into the bedroom! Marti was not shy. She was fantastic company; very funny. Sometimes infuriating, but one of those people who even when you’re arguing with her, you still liked her. It’s an enigmatic image. And then I found a passage from Grahame Sydney himself in which he described a fundamental quality that he aimed for in his paintings, without necessarily achieving it: a quality of mystery. So a painting, an image…this is perfect. It’s compelling: what’s going on? It implies a narrative but you can’t determine precisely what is being said, so there are elements of ambiguity that draw you into it.

Grahame Sydney, Killing House, 1983, collection of Te Manawa Museums Trust.

Everyone here was not prone to doing what they’re told, and in the extreme of not doing what they’re told are the two here, Tony Fomison and Philip Clairmont. This was taken in the late ‘70s at Tony Fomison’s house, in the Ponsonby/Freeman’s Bay area of Auckland. I knew Tony, but always sensed he was one of those people it was risky to get too close to. We always got on fine but he was prone to falling out with people. A fascinating and intriguing fellow whose paintings got better by the year. And this is the case with a few of the artists here: forty or fifty years on their paintings look better, you somehow get more from them, than you did when they were initially exhibited. But anyway, the two here: leading wildly Bohemian lives, self-destructive unfortunately, very different in terms of their personalities. Philip Clairmont was a lovely fellow; everyone liked him. One could sense his vulnerability, and he tragically took his own life in the early 1980s.

How did a person like Tony come out of the Christchurch suburbs? It’s one of those mysteries. But on the other hand it’s not, because typically – and I don’t want to be reductive here – a lot of these artists here had a sense of being artists, driven to be creative, knowing that it went against mainstream currents in society. Now people are much more open and appreciative and accepting of the arts, so there’s a much bigger art world. Most of the people here grew up in a much more limited, circumscribed world in various ways. So that tension between the world of art and mainstream society was very strong in the ‘60s and ‘70s. Growing up in that period I can recall it well. Both individually and collectively, these are portraits of a social climate too. This morning what immediately struck me was it’s more than just the artist’s world or a particular Boho social milieu in Auckland; it was a generally chaotic world, a kind of collective madness at times. It’s a brilliant visualisation of a broader social climate: tense, highly conflictive – much more than New Zealand society now.

Quite a number of these people Marti took photographs over a period, on several occasions, as with Gordon Walters. You couldn’t think of a more different sort of person from [Fomison and Clairmont]. Interestingly, Tony Fomison was a great admirer of Gordon Walters’ work; they got on well. Gordon was a quiet, modest, self-effacing sort of man, the opposite of Tony Fomison, so they each respected what the other was doing.

What strikes me so much, going round from person to person, is how strikingly individual these various artists are (or were). Marti could be extremely witty, and it’s often an understated wit. A book was going to be published and they wanted to include a photo she took in the ‘70s of a barbecue of MPs of the day. In the centre there’s Muldoon, and on either side of him are two Labour MPs. One is Whetu Tirakatene-Sullivan and on the other side is Hugh Watt, and they’re each brandishing what looked like machetes! Very understated, a sort of sly wit.