MADE IN GERMANY

‘Zikra’ is a rare survivor from the millions of tinplate clockwork novelties made between 1900 and 1950. They were fragile, relatively cheap and disposable.

The first toy factories emerged in Europe in the second half of the nineteenth century. This development coincided with the growth of the mass market production of consumer products and changing attitudes to childhood, particularly among the middle classes. Play became seen as educational and fantasy had a valid place in children’s lives. The publication of children’s books grew strongly in the decades before 1914 with authors such as Edith Nesbit and Frances Hodgson Burnett becoming immensely popular.

During this period, German toymaking firms dominated the world market. Protectionist lobbies in Britain tapped into prevailing anti-German feeling, complaining that “to a large and ever-increasing extent, our children’s playthings…are made in Germany.” (1). Lehmann was one such producer. Founded by Ernst Paul Lehmann in 1881, the firm was one of Germany’s largest scale toy manufacturers with exports amounting to 90% of production (2). Its specialty was quirky tinplate novelties driven by a simple clockwork motor powered by a piano wire spring. Additional movements – a waving hand or a bucking zebra – were controlled by linkages to the mechanism.

An example of a Lehmann toy, “The Anxious Bride.” The tricycle proceeds erratically while the bride, linked by a crank in the cart’s axle, rises in her seal and waves a handkerchief at the driver.

CHEAP AND CHEERFUL

Te Manawa’s ‘Zikra’ zebra-drawn cart is a typical Lehmann production. The toy was made between 1924 and 1935 and was similar in style and construction to an earlier model in which the cart was pulled by a mule. The Lehmann catalogue describes the toy as “[a] Mexican zebra team. The zebra refuses to be tamed and leaps about wildly.” Cieslik believes that it might have been inspired by an unsuccessful German stud farm in Dar es Salaam that attempted to cross-breed zebra with domesticated horses (3).

Like all tin toys, ‘Zikra’ is made from sheets of tinplated and chromolithographed mild steel. Each panel was pressed into a mould using a shaped die to create a particular part – a zebra’s leg, cart wheel, or the rider’s body. These were assembled using a system of tabs that fitted through slots in the adjoining panel and were folded over. Early presses would have been hand-operated using a central screw mechanism to raise and lower the die. Lehmann used an outline of one of these presses as its logo – see above. By the time ‘Zikra’ was made all the presses in the factory were mechanised and powered using a series of belts and shafts driven by a stationary engine in the basement. (4)

Some German toy manufacturers, notably Märklin and Bing, made expensive, high quality toys that were partly hand finished. Lehmann’s success was based on cheap toys manufactured in large quantities. In 1914, 10,000 units were made of a single toy, a clockwork motorcyclist. A 1924 price list aimed at UK retailers shows that most items were priced at between five shillings and one pound per dozen (5). ‘Zikra’ does not appear on this list but a near-identical toy, ‘The Stubborn Donkey,’ is listed at sixteen shillings a dozen. These were Christmas stocking fillers or occasional gifts from indulgent grandparents and cost between five and ten shillings each from retailers. In Europe large numbers were sold by street vendors or on stalls at town markets. (6)

All tin toys, regardless of when and where they were made, are inherently fragile and easily damaged by rough handling. Clockwork examples such as ‘Zikra’ are powered by a mechanism built into the model so that it cannot be adjusted or repaired. When something broke, the toy would be thrown away. Their short lives explain why so few remain extant. Lehmann may have made millions of clockwork novelties between 1881 and 1945, but any that made it into the 21st century intact can be worth well over $1,000 to collectors.

A boxed example of the ‘Zikra’ toy. Note the Lehmann hand press logo in the top right hand corner of the box.

The underside of a ‘Zikra’ toy. The winding key is permanently fixed to its shaft and the driving spring is simply a length of coiled piano wire. The rider is linked to rods attached to a crank on the cart’s axle, causing him to rise and then fall back into his seat. The reins are adjusted so that the unfortunate zebra is alternately yanked and released, causing it to buck.

THE PATRIOTIC TOYMAKER

Ernst Paul Lehmann was a product of the new, dynamic German Empire founded in 1871. Between 1871 and 1914 Germany emulated Britain in becoming a modern industrialised power and German products became known worldwide. Lehmann was immensely proud of his role as one of the ‘Founders’ of the new Germany. The walls of his factory carried boosterish slogans such as “Germany to the Fore!” After becoming a Brandenburg Municipal Councillor in 1900 he pushed for a memorial watchtower to be built in honour of Otto von Bismarck, a native of Brandenburg and the architect of German unification.

READING THE MARKET

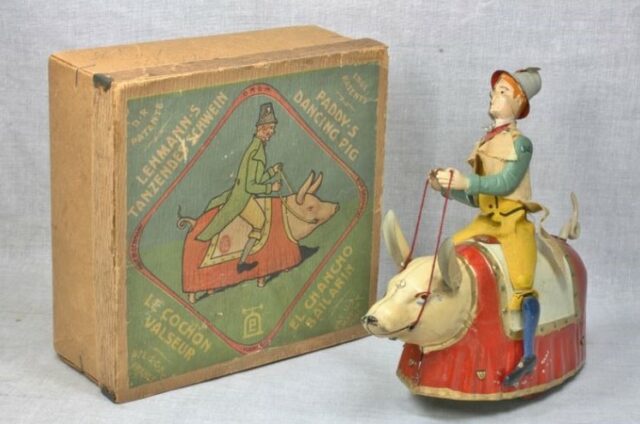

Ernst Lehmann was a shrewd operator. He attended toy makers’ conferences worldwide and had a good eye for market placement. He exported more of his production than any other German toymaker. A tap dancing figure of a Black man sold under the name ‘Oh My’ was renamed for the American market (the name containing a racial slur). A man astride a pig which spun around in circles was ‘The Dancing Pig’ for all European markets except Britain, where it became ‘Paddy’s Dancing Pig.’ To English eyes the figure would have been instantly recognisable as the Irishman of political cartoons with his distinctive hat, tailcoat and breeches.

The Lehmann factory stood in Brandenburg, a city some sixty kilometres west of Berlin. It was run on similar lines to all early 20th century factories producing mass-market consumer goods. 90% of the assembly line staff were women paid on the basis of their output. Salaried positions were held largely by men. Such was the level of industrial espionage among toy manufacturers that Ernst Lehmann patented every feature of a new toy before it left the developmental stage. Even employees were kept in the dark in case they were headhunted by the opposition. The firm’s success was based on the cheapness of its products and the enduring appeal of automata – mechanical creations which mimic human or animal actions.

Perfect market placement. This toy is ‘The Dancing Pig’ in German, French and Spanish, but ‘Paddy’s Dancing Pig’ in English.

NEW DIRECTIONS

Ernst Paul Lehmann died in 1934. Unlike many family firms in which the second generation lacked the verve of their creators, Lehmann was fortunate. The factory was inherited by Ernst Lehmann’s cousin Johannes Richter, a talented entrepreneur in his own right. Disaster came after the war when Brandenburg became part of the new East Germany. Richter fled to the west and slowly resumed production in Nuremberg. Competition came from Japan, whose tin toy firms flouted Lehmann’s patents with such regularity that the company could no longer afford to defend them. Richter’s sons Wolfgang and Eberhard responded by pivoting the company 180 degrees and introducing an expensive large scale garden railway in 1965. The new product was named LGB – Lehmann Gross-Bahn.

Initially LGB thrived. However, like many nationally based companies, it fell victim to globalisation. After being swallowed by local rival Märklin, both brands succumbed to toy giant Simba Dickie in 2013. Production is located in Hungary.

An LGB tank locomotive and wagons. Finely made and costing thousands of dollars, nothing can be further from the cheap and cheerful creations of Ernst Lehmann.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Collectors’ Club of Great Britain; Lehmann Toys

Barton, Christopher P. and Summerville, Kyle; Historical Racialised Toys in the United States. Routledge, 2016

Grove Encyclopedia of the Decorative Arts; OUP 2006

Hamlin, David D, Work and Play; the Production and Consumption of Toys in Germany, 1870 – 1914. University of Michigan Press, 2007

Brown, Kenneth D.; Factory of Dreams; A History of Meccano Ltd, 1901 – 1979; Crucible Books, 2007

Cieslik, Juren and Marianne, The History of EP Lehmann, 1881 – 1981. New Cavendish, 1982

Pressland, David, The Art of the Tin Toy. Crown, 1976

FOOTNOTES

1 Kenneth Brown, p.20

2 Antalya Toy Museum

3 Cieslik, 118 – 19

4 Cieslik, p 186

5 Cieslik, p. 185

6 Cieslik, pp 117- 18